Back to the Holodeck

The future of storytelling, if we are to take Murray seriously, isn’t about simply telling stories. It’s about telling stories that are immersive in their depth, richness, and accessibility.

In short, he so buried himself in his books that he spent the night reading from twilight till daybreak and the days, from dawn till dark; and so from little sleep and much reading, his brain dried up and he lost his wits. He filled his mind with all that he read in them, with enchantments, quarrels, battles, challenges, wounds, wooing, loves, torments, and other impossible nonsense; and so deeply did he steep his imagination in the belief that all the fanciful stuff he read was true, that to his mind no history in the world was more authentic. — Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote, pp. 20–21

When I first read Janet H. Murray’s Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace, I felt like it had spoken to a part of me that I didn’t know existed as a storyteller. Murray’s wit and depth of knowledge made this academic treatise meets storytelling manifesto an instant classic in my mind. Murray’s text also forced me to reconsider the nature of storytelling in the twenty-first century. The future of storytelling, if we are to take Murray seriously, isn’t about simply telling stories. It’s about telling stories that are immersive in their depth, richness, and accessibility. Moreover, to add to what Murray is saying in Hamlet on the Holodeck, the story becomes less about a single author, artist, or creator creating, but, instead, about collaboration between various individuals (and technologies). In other words, a real-world or universe is created in such a way that there is a blurring between the lines of reality and fiction. There is a blurring in the distinction of ownership. And, lastly, there is no end to the story. Instead, the story simply exists beyond the bounds of a single medium, a single chapter. If we are to create the future of storytelling now, we will need to embrace immersive, collaboration-oriented storytelling.

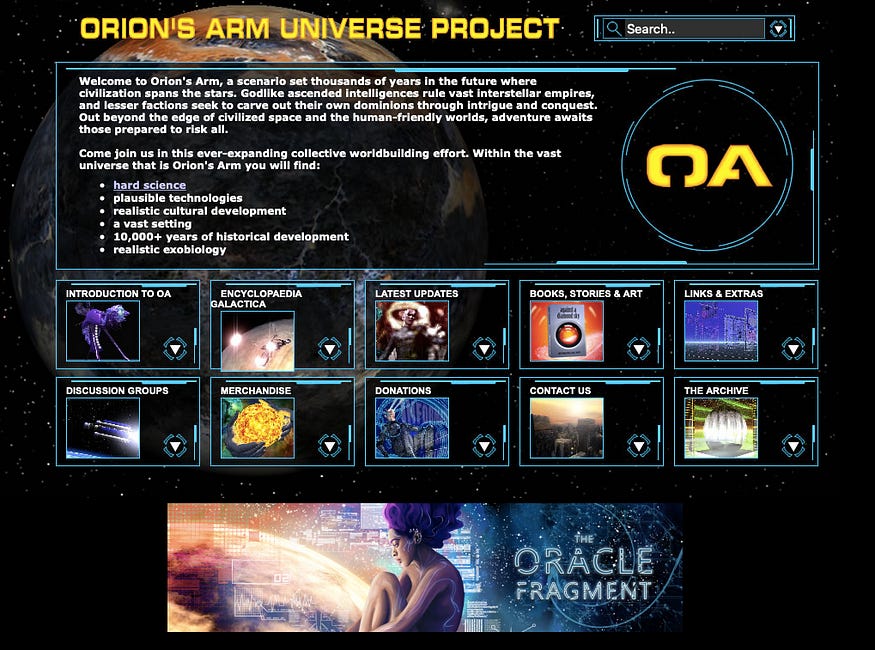

The thing about storytelling is that it hasn’t changed much. We still tell stories in a similar fashion that we were telling them centuries ago. However, that is changing with the rise of collaborative world-building projects like Orion’s Arm Universe Project, the hard-to-kill EU of the Star Wars franchise, and, of course, the prevalence of wikis driving collaboration between strangers and like-minded individuals. In other words, storytelling is entering a new era, an era in which the story doesn’t necessarily belong to a single individual but to a group of individuals with varied experiences, education levels, and the like.

Screenshot Taken of the Orion’s Arm Universe Project

Despite changes in storytelling delivery methods, we are seeing something being renewed. Maybe I am shooting myself in the foot here by saying this, but here it goes. Maybe, just maybe, we are returning to an era of storytelling that once existed before our mass media-saturated entertainment ecosystem. In other words, we are, in some respects, entering an era in which ownership over a given story isn’t as cut and dry as it might have been during the height of the golden age of mass media. To complicate matters, we live in a media ecosystem that is dominated by mediums like video games, movies, television, graphic novels, novels, and, now, world-building projects and fanfiction. Thus, our storytelling landscape is quite rich and diverse. It allows a fictional universe like Star Wars to be experienced in a plethora of ways. You can watch Jedi fight Sith lords on the silver screen. You can play out your favorite battles with the help of powerful game engines. You can become a part of the Star Wars universe, immersed in its lore, its conflicts, and its richness. The dividing lines between reality and fiction become blurred. Your need to return to the fictional universe grows stronger. It is no longer a product you are simply buying to consume. Instead, it becomes something that is part of you, something where you have a stake in the ownership.

What the diverse range of storytelling experiences tells us is that storytelling is no longer a single author, artist, or creator affair. Instead, it becomes the realm of collaboration between individuals. Further, a truly immersive experience can exist now, because the richness, the textures, and the possibilities within a given universe are expanded upon in an infinite number of ways with the help of a large number of stakeholders. Instead, of embracing this fact, many creators are resisting it. A prime example is George R. R. Martin and his Game of Thrones universe. Martin has been a loud opponent of fanfiction and fan appropriation of his characters.

Another example would be Disney’s crime against the EU of Star Wars. Instead of embracing the rich, vibrant universe created over several decades, Disney has decided to prune the old EU, creating their own. This means they took unilateral action that hurt fans, and, consequently, their bottom line. There is no doubt that Disney made back its investment; however, Disney could have created a unique business opportunity by expanding the number of stakeholders in the Star Wars universe. Instead of making decisions that are beholden to stockholders, Disney should be making decisions that keep fans, those loyal fans who have spent billions, in the loop of creation. The greatest travesty against storytelling has been the lack of cooperation and collaboration with fans to create storytelling universes that not only immerse fans in the fiction but also offer them a chance at ownership. Ownership is important in a world where the digital realm is eroding our traditional norms concerning what we own. We no longer own music. Instead, we own the access to play our music on X number of devices. The same goes for books and games. Franchises could rake in the dough by offering fans an opportunity to have a stake in something that feels real to them. Failure to do so will likely result in the decline and slow rot of once-popular franchises.

More and more, storytelling has become the art of world building, as artists create compelling environments that cannot be fully explored or exhausted within a single work or even a single medium. The world is bigger than the film, bigger than the franchise — since fan speculations and elaborations also expand the world in a variety of ways. –Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture (2006), p. 114

The future of storytelling is here — it’s just not fully acknowledged and accepted. The future of storytelling, as I and others envision it, is one in which fans are co-creators and stakeholders. Think: Orion’s Arm Universe Project. Here everyone has an opportunity to push the story universe in unique directions. Moreover, the stakeholders aren’t worried, necessarily, about being pushed away in the name of propitiating stockholders. The other aspect of storytelling, which is already evident in much of the mediums we already consume, is immersion. However, the immersion we will see in future franchises will push the lines between reality and fiction. The very boundaries of the fictional universes/worlds will be pushed to their limits, creating fantastic storytelling opportunities for franchises and fans alike.

Where do we go from here? To answer this question, I am going to look back on my experiences within the Star Frontiers and Star Wars communities during the early 2000s. Back in 2006–2009, I began my journey into fandom and world-building. Although Star Frontiers had been abandoned by its owner, Hasbro, the fans breathed new life into the universe and the game that created this universe. As fans of a dead universe, we were able to appropriate the universe for our benefit, creating fanfiction, home-brew rules, and even new worlds and new species to include in our Star Frontiers games. Around the same time, I participated in the Star Wars EU by playing around on Wookiepedia, a rather large wiki project, with thousands of fans collaborating to catalog the farthest reaches of the Star Wars universe. These two universes provide important lessons in what companies and creators can do to engage fans (i.e., consumers) in unique ways. Hasbro’s hands-off approach to the Star Frontiers universe allowed people to explore their favorite universe without bumping up against official canon or strict fan creation policies of the original creator or owner of the franchise. Before the Disney takeover of the Star Wars franchise, there was a sort of limited hands-off approach to the fan-favorite universe. Yes, the original creator(s) held Star Wars close, but they seemed to care about fan ownership as well. Fans made the Star Wars universe what it was. To a younger me, I felt free to explore the boundaries of the Star Wars universe. The older me feels as if the franchise has tightened its grip and constrained fan ownership within the universe.

Narrative imagining — story — is the fundamental instrument of thought. Rational capacities depend upon it. It is our chief means of looking into the future, or predicting, of planning, and of explaining. — Mark Turner

Those looking to create immersive, collaborative-driven universes should take note of the approaches pushed by George R. R. Martin and Disney. Yes, these universes (i.e., Game of Thrones and Star Wars) are, technically speaking, the creation of their original creators. However, fans have latched onto these universes not because they wish to profit from their fan fiction or world-building, but because they wish to explore their favorite worlds or universes beyond the confines of a given book series, television show, or the fully sanctioned portions of the universe. Thus, creators should offer fans immersive, collaborative-driven universes, to allow fans to have a stake and to create a loyal fanbase that could be brought to bear when it is time to make money. Creators could offer fans opportunities to create wikis, world-building projects, and fan fiction that could have a real impact on the universes or worlds they cherish. Moreover, creators could offer fans the opportunities to truly explore their cherished universes and worlds without censorship by offering inexpensive or open licenses for fan-created products. (I credit Dungeons & Dragons for leading this in their game multiverse, where fans have the opportunity to create original content within the game’s structure.) Creators could even offer their fanbases opportunities to fashion branching universes, allowing fans to explore different outcomes, and different storytelling experiences, without the threat of legal action.

We must go back to the days of the campfire, where people could claim ownership over the very stories they heard and told around the fire. We need the campfires again because we need to reestablish a sense of belonging that is missing from our world today. We need to go back to the golden years of fan fiction, where fans could (without fear) contribute their renditions, and their explorations, of their favorite worlds/universes. In other words, we need to push back against the entertainment monopolies, and we need to allow fans to have ownership again. If we are to build truly immersive and collaborative-driven worlds/universes, we will need to rethink ownership over the story and the content within a story’s universe/world. To do so is not to strip away the profitability of the franchises businesses create. Instead, doing so will create profitable businesses that cherish fans and collaborate with fans. It’s best to remember that fans are the heart and soul of any franchise. To walk away from this realization, to distance one’s self and business from this notion, would be akin to business suicide.

To Err Is Human is a blog by G. Michael Rapp (and visiting writers and content creators). Copyright 2024. All rights reserved. However, if you're using any content to add to an ongoing conversation, for teaching purposes, and/or for furthering the hobbies of gaming, storytelling, and worldbuilding, feel free to pull what you want from this blog, so long as you give credit to the original website (https://toerrishuman.xyz) and the author(s)/content creators in question.